“In 1918, at the end of four years of World War I’s devastation, leaders negotiated for the guns in Europe to fall silent once and for all on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. It was not technically the end of the war, which came with the Treaty of Versailles. Leaders signed that treaty on June 28, 1919, five years to the day after the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand set off the conflict. But the armistice declared on November 11 held, and Armistice Day became popularly known as the day “The Great War,” which killed at least 40 million people, ended.

In 1954, to honor the armed forces of wars after World War I, Congress amended the law creating what had been known as Armistice Day by striking out the word “armistice” and putting “veterans” in its place. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, himself a veteran who had served as the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and who had become a five-star general of the Army before his political career, later issued a proclamation asking Americans to observe Veterans Day: “Let us solemnly remember the sacrifices of all those who fought so valiantly, on the seas, in the air, and on foreign shores, to preserve our heritage of freedom, and let us reconsecrate ourselves to the task of promoting an enduring peace so that their efforts shall not have been in vain.” Heather Cox Richardson[1]:

The first person killed at the Boston Massacre, which spurred the American Revolution, was Crispus Attucks, a Black American patriot. Over the entire course of this country’s history, Black Americans have been sought after during times of war. Today, Black Americans represent about 16% of the total armed forces -slightly higher than the 13% representation in the general populace. Many Black Americans volunteered for duty and combat in the belief that America would recognize them as full, loyal, and worthy Americans and as a chance to show they are the equal of white men or women. But they were wrong and their return home often did not go as planned. White supremacist hate groups and individual racists were more alarmed than ever. They feared that given a partial taste of equality and being trained in the use of firearms, that “their Negroes” might expect some greater form of equality, respect, and gratitude back home. And they did. Returning Black veterans were often targeted for increased violence, not respect and gratitude.

Good, bad, and ugly, America has some interesting history. Here’s some that pertains to veterans.

Port Chicago

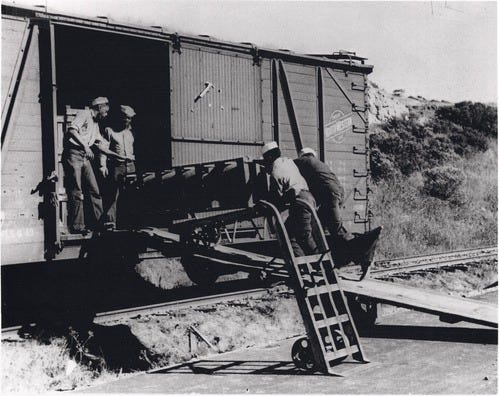

A few years ago I was privileged to get the VIP tour of Port Chicago Naval shipyard - located on the East Bay, across from San Francisco – by the Superintendent of the Port Chicago National Monument, Tom Leatherman. During WWII the shipyard was devoted to transferring munitions delivered by rail and then loading them onto ships bound for the war in Europe and Japan. On July 17th, 1944 there was a massive explosion that blew apart 320 sailors and civilians and injured almost 400 others.

During the war, Black Americans were recruited with the promise that they would be offered the same job specialties as their White counterparts. But in reality, Black sailors were assigned almost exclusively to positions as stewards - essentially kitchen and dining room workers; and stevedores - dock laborers. Thus it is not surprising that of those who died, 202 were Black as were 233 of those that were injured.

On the evening of July 17, empty merchant ship SS Quinault Victory was prepared for loading on her maiden voyage. The SS E.A. Bryan, another merchant ship, had just returned from her first voyage and was loading across the platform from Quinault Victory. The holds were packed with high explosive and incendiary bombs, depth charges and ammunition -- 4,606 tons of ammunition in all. There were 16 rail cars on the pier with another 429 tons. Working in the area were 320 cargo handlers, crewmen and sailors.

At 10:18 p.m., an explosion ripped apart the night sky. Witnesses said that a brilliant white flash shot into the air, accompanied by a loud, sharp report. Flashing like fireworks, smaller explosions went off in the cloud as it rose. Within six seconds, a deeper explosion erupted as the contents of the E.A. Bryan detonated in one massive explosion. The seismic shock wave was felt as far away as Boulder City, Nevada.

The E.A. Bryan and the structures around the pier were completely disintegrated. A pillar of fire and smoke stretched more than two miles into the sky above Port Chicago. The largest remaining pieces of the 7,200-ton ship were the size of a suitcase. A plane flying at 9,000 feet reported seeing chunks of white hot metal "as big as a house" flying past. The shattered Quinault Victory was spun into the air. Witnesses reported seeing a 200-foot column on which rode the bow of the ship, its mast still attached. Its remains crashed back into the bay 500 feet away.

All 320 men on duty that night were killed instantly. The blast smashed buildings and rail cars near the pier and damaged every building in Port Chicago. People on the base and in town were sent flying or were sprayed with splinters of glass and other debris. The air filled with the sharp cracks and dull thuds of smoldering metal and unexploded shells as they showered back to Earth as far as two miles away. The blast caused damage 48 miles across the bay in San Francisco.

Munitions handling was dangerous work, yet no enlisted men stationed at Port Chicago had received formal training in the handling and loading of explosives into ships. Even the officers had not received training. Lieutenant Commander Alexander Holman, loading officer at Port Chicago whose duties included officer training, had initiated a search for training materials and samples, but had not organized a training class.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union responded to word of unsafe practices on the base by offering to bring in experienced men to train the battalion. But Navy leadership declined the offer fearing higher costs, slower pace, and possible sabotage from civilian longshoremen angling to do the work themselves.

The disaster sparked controversy in its aftermath. It was determined that inadequate training, hazardous conditions and irresponsible labor practices contributed to the disaster. Many of the surviving sailors felt that their commanders had not properly addressed these issues when they asked them to continue to work. In response, they protested with a work stoppage. Although no violence or threat of violence occurred, the Navy viewed the work stoppage as a mutiny. In September 1944, the Navy charged 50 of the Port Chicago sailors with disobeying orders and initiating a mutiny. A court-martial found them guilty in October.

Some of the men who had been named as having been given direct orders to work testified that they had not been given any such order. Seaman Ollie E. Green—who had accidentally broken his wrist one day prior to the first work-stoppage on August 9—said that though he had heard an officer in prior testimony name him as one who had been given a direct order, the officer had only asked him how his wrist was doing, to which he responded "not so good."

At the end of his testimony, Green told the court that he was afraid to load ammunition because of "them officers racing each division to see who put on the most tonnage, and I knowed the way they was handling ammunition it was liable to go off again. If we didn't want to work fast at that time, they wanted to put us in the brig, and when the Executive Officer came down on the docks, they wanted us to slow up."[14] This was the first that the newspaper reporters had heard of speed and tonnage competition between divisions at Port Chicago, and each reporter filed a story featuring this revelation to be published the next day. Naval authorities quickly issued a statement denying Green's allegation.

Beginning in 1990, a campaign led by 25 U.S. congressmen was unsuccessful in having the convicts exonerated. Gordon Koller, Chief Petty Officer at the time of the explosion, was interviewed in 1990. Koller stated that the hundreds of men like him who continued to load ammunition in the face of danger were "the ones who should be recognized". In 1994, the Navy rejected a request by four California lawmakers to overturn the courts-martial decisions. The Navy found that racial inequities were responsible for the sailors' ammunition-loading assignments but that no prejudice occurred at the courts-martial.

In the 1990s, Freddie Meeks, one of the few still alive among the group of 50, was urged to petition the president for a pardon. Others of the Port Chicago 50 had refused to ask for a pardon, reasoning that a pardon is for guilty people receiving forgiveness; they continued to hold the position that they were not guilty of mutiny. Meeks pushed for a pardon as a way to get the story out, saying "I hope that all of America knows about it... it's something that's been in the closet for so long." In September 1999, the petition by Meeks was bolstered by 37 members of Congress including George Miller, the U.S. representative for the district containing the disaster site. The 37 congressmen sent a letter to President Bill Clinton and in December 1999, Clinton pardoned Meeks, who died in June 2003. Efforts to posthumously exonerate all 50 sailors continued.

On June 11, 2019, a concurrent resolution sponsored by U.S. Mark DeSaulnier was introduced in the 116thU.S. Congress. The resolution is intended to recognize the victims of the explosion and officially exonerate the 50 men court-martialed by the Navy.

Finally, on July 17, 2024, the 80th anniversary of the explosion, the United States Navy exonerated the remaining 256 men, including the "Port Chicago 50". The General Counsel of the Navy determined that multiple errors had occurred during the courts-martial, including that the sailors were denied a meaningful right to counsel. Due to the exoneration, all dishonorable discharges tied to the courts-martial were vacated.

The disaster at Port Chicago and its aftermath are important moments in Black history. The events caught the attention of civil rights activist and chief counsel of the NAACP, Thurgood Marshall. He believed that the court-martial unjustly charged the sailors with mutiny.

Furthermore, he called for a government investigation of the Navy’s practice of assigning Black service members to segregated support roles, as well as the unsafe conditions in which the sailors worked. Bringing national attention to these issues contributed to the executive order that desegregated the military in 1948. Of course, it took decades – and the military is still working at it – to actually desegregate the armed forces.

Sgt. Isaac Woodard Jr., 26, was a decorated African-American veteran. He had just been honorably discharged from the United States Army in 1946 and was headed home to Winnsboro, S.C. from Camp Gordon in GA. Sgt. Woodard and the bus driver argued after Woodard asked to take a bathroom break. Although the bus company’s policy required drivers to accommodate such requests, the driver refused. An argument ensued which led the driver to call the police when they stopped in Batesburg, 35 miles southwest of Columbia.

The police chief, Lynwood Shull, and another officer dragged Sgt. Woodard off the bus, still in uniform, and beat him severely. Chief Shull beat Sgt Woodward so violently, jamming the ends of his nightstick into Sgt. Woodard’s eyes, that he broke his nightstick and permanently blinded Sgt Woodward.

The next morning, Sgt. Woodard was dragged before the local judge where he was convicted of drunken and disorderly conduct and fined $50.

Sgt. Woodard recovered in a veteran’s hospital and eventually moved to New York without his wife, who walked out on the marriage after the incident. His family in New York helped to care for him until his death at 73 in 1992.

On July 24, 1944, Jackie Robinson, a 25-year-old Black American lieutenant with the 761st Tank Battalion, boarded a shuttle bus in front of the Black officers’ club at Camp Hood, Texas, and took a seat halfway down the aisle. Five stops later, the civilian driver ordered him to the back of the bus, as was the custom in states that enforced racial segregation. Robinson refused to move. He was a commissioned U.S. Army officer on a U.S. Army base and saw no reason why he couldn’t sit where he wanted. When Robinson didn’t budge, the driver promised to make trouble once the bus reached its destination.

Black men had fought in every war since the Revolution, but the armed services didn’t treat them the same as white men. Segregation was the rule. A flashpoint for racial tension was bus service at military bases. Soldiers, both Black and White, relied on buses, usually operated by civilian companies. Shuttles transported soldiers inside sprawling bases, and buses were necessary to travel to the nearest towns, often miles from camp. Civilians working on military bases also rode these buses. In areas of the country where Jim Crow laws and customs prevailed, Black soldiers were relegated to the back of the bus, even on army bases.

“The South,” Time Magazine reported, was “prepared to back up its Jim Crow laws with force.” On July 28, 1942, in Beaumont, Texas, police officers beat and shot Private Charles J. Reco for refusing to leave his seat in the White section of a bus. On March 13, 1944, a driver in Alexandria, Louisiana, shot and killed Private Edward Green for failing to move to the back of the bus.

Robinson had broken his right ankle playing football in 1937. The injury had not healed properly, and Robinson had aggravated it on an army obstacle course in 1943. In January 1944, an army medical board had found him fit only for limited duty and recommended against strenuous use of his right leg. He was ordered to McCloskey General Hospital in Temple, Texas, on June 21, 1944, for a final decision on his fitness for combat.

On July 6, while still being assessed at the hospital, Robinson, who didn’t drink, traveled to Camp Hood to visit friends at the Black officers’ club. He left at 10 p.m., planning to take a bus to the base’s central station and then hop on another for the 30-mile trip back to the hospital.

Robinson boarded a shuttle driven by a civilian, Milton Renegar, saw a familiar face, and sat next to her in the midsection of the bus. She was Virginia Jones, the wife of another Black officer in the 761st and a woman Robinson described as “very fair” and often mistaken for white. Five stops later, Renegar ordered Robinson to the back of the bus. Renegar expected white women to board at the following stops, he said later, and didn’t think they’d want to sit near a Black man. Texas law required Black Americans to sit in the back, but Robinson refused to move. He grudgingly obeyed Jim Crow rules while off post, but not on an army base.

When the bus arrived at the station, the MPs were called. A hostile crowd had gathered so the MP took Robinson and a couple of witnesses to the guard shack where the witnesses described Robinson as profane and out-of-control.

Eventually the Army charged Robinson with two offenses, neither of which related to the bus seating incident. The first alleged that he had acted in an “insolent, impertinent and rude manner” to a superior officer. The second claimed that he had disobeyed a direct order form the same officer while being detained in the guard shack.

For the army, the case came at a bad time. Two days after the incident, on July 8, 1944, the army had formally outlawed segregation on buses at military bases. “Restricting personnel to certain sections of such transportation because of race,” the directive stated, “will not be permitted either on or off a post, camp, or station, regardless of local civilian custom.” That same day, in Durham, North Carolina, a bus driver killed Private Booker T. Spicely after he had balked at going to the back of the bus. The army was in the awkward position of prosecuting charges against Robinson that arose from the enforcement of a Jim Crow rule that it now condemned and that had cost Spicely his life.

Robinson’s court martial took place at Camp Hood on August 2, 1944. Because the charges were limited to Robinson’s conduct in the guard room, the judges would hear nothing about the incident on the bus and little about events at the depot.

The prosecution called the superior officer, who described Robinson’s conduct on July 6 as disrespectful and disobedient, and a female passenger on the bus who had told Robinson that he didn’t know his place, corroborated the testimony. Robinson took the stand and denied the officer’s account. He also told the judges just how hateful another witness had been while in the guard shack. Robinson said his grandmother, a former slave, had told him that “The definition of the word nigger was a low, uncouth person.” “Sirs, I don’t consider that I am low and uncouth.”

The judges acquitted Robinson on both counts. Although he had been cleared, Robinson’s military career was effectively over. Two weeks earlier, on July 21, 1944, army doctors had decided that his ankle injury was permanent. His outfit, “The Black Panthers” had already deployed to fight in Europe from October 31, 1944, through May 6, 1945, and earned a Presidential Unit Citation. With his outfit gone and a bad taste lingering from the court-martial, Robinson asked to be discharged because of his ankle injury.

The rest of the Jackie Robinson story is history. Major league baseball owners had a long-standing agreement to keep baseball white, but the Dodgers intended to change that, and manager Branch Rickey was searching for the right player to break the color barrier. In addition to a talented athlete, Rickey wanted a man of unimpeachable character and firm inner strength. He knew that player would have to endure the vilest of racial slurs from fans and opposing players and, in some cities, he would be barred from the hotels and restaurants where his white teammates stayed and ate. Rickey found all of that in Jackie Robinson.

If you have any means left after this last election and you want to support this nonprofit, co-founded by a veteran, please click on the donation button above.

Sources:

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/port-chicago-disaster

https://www.nps.gov/poch/index.htm

https://www.nps.gov/poch/learn/photosmultimedia/multimedia.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Chicago_disaster

https://www.military.com/history/port-chicago-disaster-remembered.html

Been thinking a lot about you lately and am grateful for your continued insights and wisdom.